Loading, please wait.

Loading, please wait.

Atlas Table of Contents

Osteology.

The Skeleton of the Trunk.

Fig. A1

Fig. A2

Fig. A3

Fig. A4

Fig. A5

Fig. A6

Fig. A7

Fig. A8

Fig. A9

Fig. A10

Fig. A11

Fig. A12

Fig. A13

Fig. A14

Fig. A15

Fig. A16

Fig. A17

Fig. A18

Fig. A19

Fig. A20

Fig. A21

Fig. A22

Fig. A23

Fig. A24

Fig. A25

Fig. A26

Fig. A27

Fig. A28

Fig. A29

Fig. A30

Fig. A31

Fig. A32

Fig. A33

Fig. A34

Fig. A35

Fig. A36

Fig. A37

Fig. A38

Fig. A39

Fig. A40

Fig. A41

The Skull and the Skull Bones.

Fig. A42

Fig. A43

Fig. A44

Fig. A45

Fig. A46

Fig. A47

Fig. A48

Fig. A49

Fig. A50

Fig. A51

Fig. A52

Fig. A53

Fig. A54

Fig. A55

Fig. A56

Fig. A57

Fig. A58

Fig. A59

Fig. A60

Fig. A61

Fig. A62

Fig. A63

Fig. A64

Fig. A65

Fig. A66

Fig. A67

Fig. A68

Fig. A69

Fig. A70

Fig. A71

Fig. A72

Fig. A73

Fig. A74

Fig. A75

Fig. A76

Fig. A77

Fig. A78

Fig. A79

Fig. A80

Fig. A81

Fig. A82

Fig. A83

Fig. A84

Fig. A85

Fig. A86

Fig. A87

Fig. A88

Fig. A89

Fig. A90

Fig. A91

Fig. A92

Fig. A93

Fig. A94

Fig. A95

Fig. A96

Fig. A97

Fig. A98

Fig. A99

Fig. A100

Fig. A101

Fig. A102

Fig. A103

Fig. A104

Fig. A105

Fig. A106

Fig. A107

Fig. A108

Fig. A109

Fig. A110

Fig. A111

Fig. A112

Fig. A113

Fig. A114

Fig. A115

The Appendicular Skeleton.

Fig. A116

Fig. A117

Fig. A118

Fig. A119

Fig. A120

Fig. A121

Fig. A122

Fig. A123

Fig. A124

Fig. A125

Fig. A126

Fig. A127

Fig. A128

Fig. A129

Fig. A130

Fig. A131

Fig. A132

Fig. A133

Fig. A134

Fig. A135

Fig. A136

Fig. A137

Fig. A138

Fig. A139

Fig. A140

Fig. A141

Fig. A142

Fig. A143

Fig. A144

Fig. A145

Fig. A146

Fig. A147

Fig. A148

Fig. A149

Fig. A150

Fig. A151

Fig. A152

Fig. A153

Fig. A154

Fig. A155

Fig. A156

Fig. A157

Fig. A158

Fig. A159

Fig. A160

Fig. A161

Fig. A162

Fig. A163

Fig. A164

Fig. A165

Fig. A166

Fig. A167

Fig. A168

Fig. A169

Fig. A170

Fig. A171

Fig. A172

Fig. A173

Fig. A174

Fig. A175

Bone Structure.

Fig. A176

Fig. A177

Fig. A178

Fig. A179

Fig. A180

Fig. A181

Röntgen Pictures of the Human Skeleton.

Fig. A182

Fig. A183

Fig. A184

Fig. A185

Fig. A186

Fig. A187

Fig. A188

Fig. A189

Fig. A190

Syndesmology.

Joints and Ligaments of the Trunk and Head.

Fig. A191

Fig. A192

Fig. A193

Fig. A194

Fig. A195

Fig. A196

Fig. A197

Fig. A198

Fig. A199

Fig. A200

Fig. A201

Fig. A202

Fig. A203

Fig. A204

Fig. A205

Fig. A206

Fig. A207

Fig. A208

Fig. A209

Fig. A210

Fig. A211

Joints and Ligaments of the Upper Extremity.

Fig. A212

Fig. A213

Fig. A214

Fig. A215

Fig. A216

Fig. A217

Fig. A218

Fig. A219

Fig. A220

Fig. A221

Fig. A222

Fig. A223

Fig. A224

Fig. A225

Joints and Ligaments of the Lower Extremity.

Fig. A226

Fig. A227

Fig. A228

Fig. A229

Fig. A230

Fig. A231

Fig. A232

Fig. A233

Fig. A234

Fig. A235

Fig. A236

Fig. A237

Fig. A238

Fig. A239

Fig. A240

Fig. A241

Fig. A242

Fig. A243

Fig. A244

Fig. A245

Fig. A246

Fig. A247

Fig. A248

Fig. A249

Fig. A250

Fig. A251

Myology.

Muscles of the Back.

Fig. A252

Fig. A253

Fig. A254

Fig. A255

Fig. A256

Fig. A257

Fig. A258

Fig. A259

Fig. A260

Muscles of the Thorax and Abdomen, including the Diaphragm and Iliopsoas.

Fig. A261

Fig. A262

Fig. A263

Fig. A264

Fig. A265

Fig. A266

Fig. A267

Fig. A268

Fig. A269

Fig. A270

Pl. A1, Fig. 1

Pl. A1, Fig. 2

Muscles of the Neck.

Fig. A271

Fig. A272

Fig. A273

Fig. A274

Fig. A275

Fig. A276

Muscles of the Head.

Fig. A277

Fig. A278

Fig. A279

Fig. A280

Fig. A281

Fig. A282

Muscles and Fasciae of the Upper Extremity.

Fig. A283

Fig. A284

Fig. A285

Fig. A286

Fig. A287

Fig. A288

Fig. A289

Fig. A290

Fig. A291

Fig. A292

Fig. A293

Fig. A294

Fig. A295

Fig. A296

Fig. A297

Fig. A298

Fig. A299

Fig. A300

Fig. A301

Fig. A302

Fig. A303

Fig. A304

Fig. A305

Fig. A306

Fig. A307

Fig. A308

Pl. A2, Fig. 1

Pl. A2, Fig. 2

Muscles and Fasciae of the Lower Extremity.

Fig. A309

Fig. A310

Fig. A311

Fig. A312

Fig. A313

Fig. A314

Fig. A315

Fig. A316

Fig. A317

Fig. A318

Fig. A319

Fig. A320

Fig. A321

Fig. A322

Fig. A323

Fig. A324

Fig. A325

Fig. A326

Fig. A327

Fig. A328

Fig. A329

Fig. A330

Fig. A331

Fig. A332

Fig. A333

Fig. A334

Fig. A335

Fig. A336

Fig. A337

Pl. A3, Fig. 1

Pl. A3, Fig. 2

Pl. A4, Fig. 1

Pl. A4, Fig. 2

Regions of the Body.

Fig. A338

Fig. A339

Fig. A340

Fig. A341

Fig. A342

Splanchnology.

Digestive Organs.

Fig. B1

Fig. B2

Fig. B3

Fig. B4

Fig. B5

Fig. B6

Fig. B7

Fig. B8

Fig. B9

Fig. B10

Fig. B11

Fig. B12

Fig. B13

Fig. B14

Fig. B15

Fig. B16

Fig. B17

Fig. B18

Fig. B19

Fig. B20

Fig. B21

Fig. B22

Fig. B23

Fig. B24

Fig. B25

Fig. B26

Fig. B27

Fig. B28

Fig. B29

Fig. B30

Fig. B31

Fig. B32

Fig. B33

Fig. B34

Fig. B35

Fig. B36

Fig. B37

Fig. B38

Fig. B39

Fig. B40

Fig. B41

Fig. B42

Fig. B43

Fig. B44

Fig. B45

Fig. B46

Fig. B47

Fig. B48

Fig. B49

Fig. B50

Fig. B51

Fig. B52

Fig. B53

Fig. B54

Fig. B55

Fig. B56

Fig. B57

Fig. B58

Fig. B59

Fig. B60

Fig. B61

Fig. B62

Fig. B63

Fig. B64

Fig. B65

Fig. B66

Fig. B67

Fig. B68

Fig. B69

Fig. B70

Fig. B71

Fig. B72

Fig. B73

Fig. B74

Fig. B75

Fig. B76

Fig. B77

Fig. B78

Fig. B79

Fig. B80

Fig. B81

Fig. B82

Fig. B83

Fig. B84

Fig. B85

Fig. B86

Fig. B87

Fig. B88

Fig. B89

Fig. B90

Peritoneum and situs viscerum.

Fig. B91

Fig. B92

Fig. B93

Fig. B94

Fig. B95

Fig. B96

Fig. B97

Fig. B98

Fig. B99

Fig. B100

Fig. B101

Fig. B102

Fig. B103

Fig. B104

Fig. B105

Fig. B106

Fig. B107

Fig. B108

Fig. B109

Fig. B110

Fig. B111

Respiratory Organs (including pleura).

Fig. B112

Fig. B113

Fig. B114

Fig. B115

Fig. B116

Fig. B117

Fig. B118

Fig. B119

Fig. B120

Fig. B121

Fig. B122

Fig. B123

Fig. B124

Fig. B125

Fig. B126

Fig. B127

Fig. B128

Fig. B129

Fig. B130

Fig. B131

Fig. B132

Fig. B133

Fig. B134

Fig. B135

Fig. B136

Fig. B137

Fig. B138

Fig. B139

Fig. B140

Fig. B141

Fig. B142

Fig. B143

Fig. B144

Fig. B145

Fig. B146

Fig. B147

Fig. B148

Fig. B149

Fig. B150

Fig. B151

Fig. B152

Fig. B153

Fig. B154

Fig. B155

Fig. B156

Fig. B157

Fig. B158

Fig. B159

Fig. B160

Fig. B161

Fig. B162

Fig. B163

Fig. B164

Fig. B165

Fig. B166

Urogenital Organs, apparatus urogenitalis.

Excretory Organs (including Suprarenal glands).

Fig. B167

Fig. B168

Fig. B169

Fig. B170

Fig. B171

Fig. B172

Fig. B173

Fig. B174

Fig. B175

Fig. B176

Fig. B177

Fig. B178

Fig. B179

Fig. B180

Fig. B181

Fig. B182

Fig. B183

Fig. B184

The Male Genitalia.

Fig. B185

Fig. B186

Fig. B187

Fig. B188

Fig. B189

Fig. B190

Fig. B191

Fig. B192

Fig. B193

Fig. B194

Fig. B195

Fig. B196

Fig. B197

Fig. B198

Fig. B199

Fig. B200

Fig. B201

Fig. B202

Fig. B203

The Female Genitalia.

Fig. B204

Fig. B205

Fig. B206

Fig. B207

Fig. B208

Fig. B209

Fig. B210

Fig. B211

Fig. B212

Fig. B213

Fig. B214

Fig. B215

Fig. B216

Fig. B217

Fig. B218

Fig. B219

Perineum.

Fig. B220

Fig. B221

Fig. B222

Fig. B223

Fig. B224

Angiology and Neurology

The Circulation of the Blood.

Fig. B225

Fig. C1

The Heart.

Fig. B226

Fig. B227

Fig. B228

Fig. B229

Fig. B230

Fig. B231

Fig. B232

Fig. B233

Fig. B234

Fig. B235

Fig. B236

Fig. B237

Fig. B238

Fig. B239

Fig. B240

Fig. B241a

Fig. B241b

Fig. B242

Fig. B243

Fig. B244

The Fetal Circulation.

Fig. C2

Fig. C3

Vessels of the Heart.

Fig. C4

Fig. C5

Nerves and Vessels of the Neck, Axilla, Back and Thoracic Wall.

Fig. C6

Fig. C7

Fig. C8

Fig. C9

Fig. C10

Fig. C11

Fig. C12

Fig. C13

Fig. C14

Fig. C15

Fig. C16

Fig. C17

Fig. C18

Fig. C19

Fig. C20

Fig. C21

Fig. C22

Fig. C23

Fig. C24

Fig. C25

Fig. C26

Fig. C27

Nerves and Vessels of the Upper Extremity.

Fig. C28

Fig. C29

Fig. C30

Fig. C31

Fig. C32

Fig. C33

Fig. C34

Fig. C35

Fig. C36

Fig. C37

Fig. C38

Fig. C39

Fig. C40

Fig. C41

Fig. C42

Fig. C43

Fig. C44

Fig. C45

Fig. C46

Fig. C47

Fig. C48

Fig. C49

Fig. C50

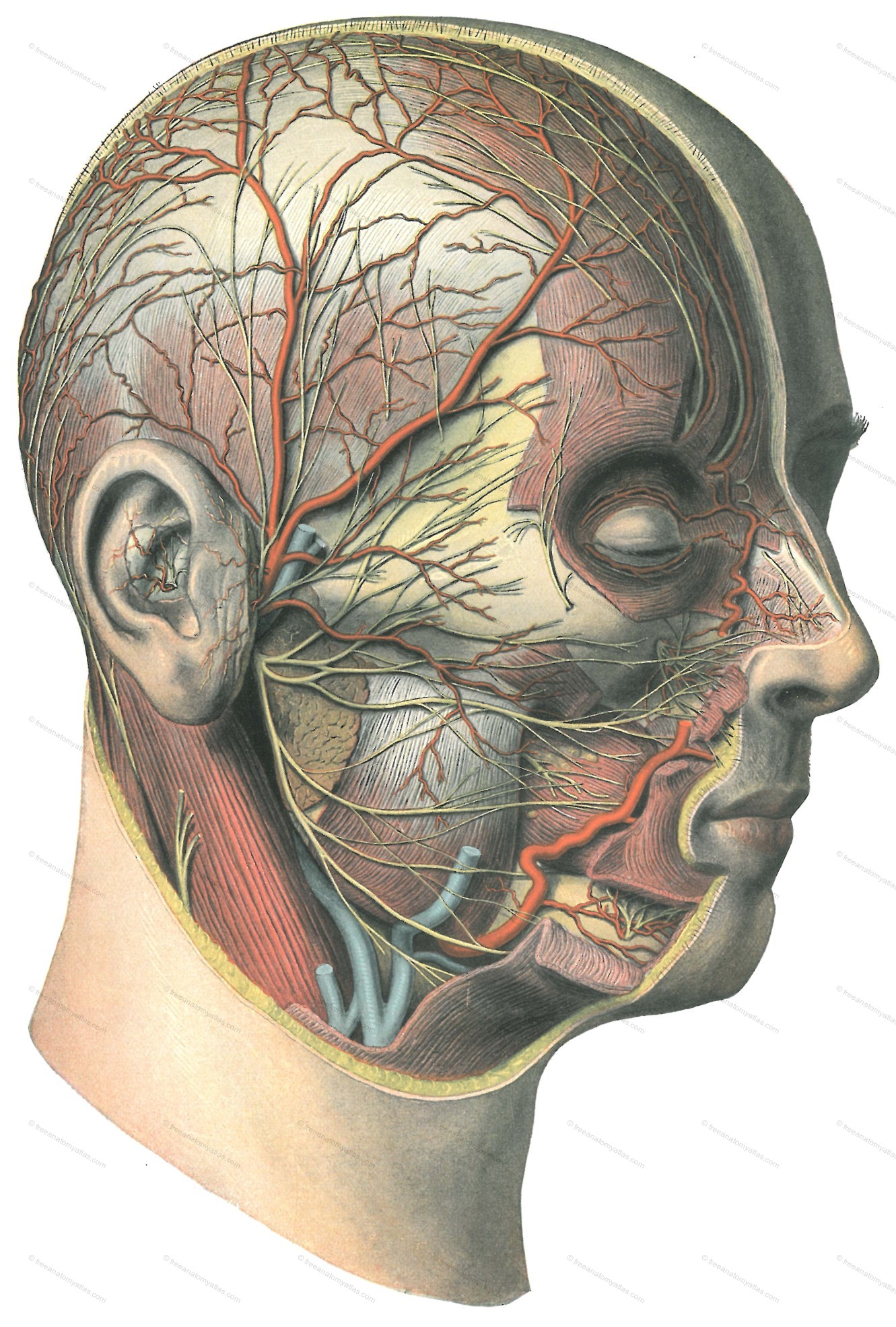

Nerves and Vessels of the Head and the Viscera of the Head and Neck.

Fig. C51

Fig. C52

Fig. C53

Fig. C54

Fig. C55

Fig. C56

Fig. C57

Fig. C58

Fig. C59

Fig. C60

Fig. C61

Fig. C62

Fig. C63

Fig. C64

Fig. C65

Fig. C66

Fig. C67

Fig. C68

Fig. C69

Fig. C70

Fig. C71

Fig. C72

Fig. C73

Fig. C74

Fig. C75

Vessels of the Abdominal Viscera.

Fig. C76

Fig. C77

Fig. C78

Fig. C79

Vessels and Nerves of the false and true Pelvis and of the Perineum.

Fig. C80

Fig. C81

Fig. C82

Fig. C83

Fig. C84

Fig. C85

Fig. C86

Fig. C87

Fig. C88

Fig. C89

Fig. C90

Nerves and Vessels of the Lower Extremity.

Fig. C91

Fig. C92

Fig. C93

Fig. C94

Fig. C95

Fig. C96

Fig. C97

Fig. C98

Fig. C99

Fig. C100

Fig. C101

Fig. C102

Fig. C103

Fig. C104

Fig. C105

Fig. C106

Fig. C107

Fig. C108

Fig. C109

Fig. C110

Fig. C111

Fig. C112

Fig. C113

The Sympathetic Nervous System.

Fig. C114

Fig. C115

Fig. C116

Fig. C117

Fig. C118

The Spinal Cord.

Fig. C119

Fig. C120

Fig. C121

Fig. C122

Fig. C123

Fig. C124

Fig. C125

Fig. C126

Fig. C127

Fig. C128

Fig. C129

Fig. C130

Fig. C131

Fig. C132

Fig. C133

Fig. C134

Meninges and Vessels of the Brain.

Fig. C135

Fig. C136

Fig. C137

Fig. C138

Fig. C139

Fig. C140

Fig. C141

Fig. C142

Fig. C143

Fig. C144

Fig. C145

Fig. C146

Fig. C147

The Brain.

Fig. C148

Fig. C149

Fig. C150

Fig. C151

Fig. C152

Fig. C153

Fig. C154

Fig. C155

Fig. C156

Fig. C157

Fig. C158

Fig. C159

Fig. C160

Fig. C161

Fig. C162

Fig. C163

Fig. C164

Fig. C165

Fig. C166

Fig. C167

Fig. C168

Fig. C169

Fig. C170

Fig. C171

Fig. C172

Fig. C173

Fig. C174

Fig. C175

Fig. C176

Fig. C177

Fig. C178

Fig. C179

Fig. C180

Fig. C181

Fig. C182

Fig. C183

Fig. C184

Fig. C185

Fig. C186

Fig. C187

Fig. C188

Fig. C189

Fig. C190

Fig. C191

Fig. C192

Fig. C193

Fig. C194

Fig. C195

Fig. C196

Fig. C197

Fig. C198

Fig. C199

Fig. C200

Fig. C201

Fig. C202

Fig. C203

Fig. C204

Fig. C205

Fig. C206

Fig. C207

Fig. C208

Fig. C209

Fig. C210

Fig. C211

Fig. C212

Fig. C213

Fig. C214

Fig. C215

Fig. C216

Fig. C217

Fig. C218

Fig. C219

Fig. C220

Fig. C221

Fig. C222

Fig. C223

Fig. C224

Fig. C225

Fig. C226

Fig. C227

Fig. C228

Fig. C229

Fig. C230

Fig. C231

Fig. C232

Fig. C233

Fig. C234

Fig. C235

Sense Organs.

The Eye.

Fig. C236

Fig. C237

Fig. C238

Fig. C239

Fig. C240

Fig. C241

Fig. C242

Fig. C243

Fig. C244

Fig. C245

Fig. C246

Fig. C247

Fig. C248

Fig. C249

Fig. C250

Fig. C251

Fig. C252

Fig. C253

Fig. C254

Fig. C255

Fig. C256

Fig. C257

Fig. C258

Fig. C259

Fig. C260

Fig. C261

Fig. C262

Fig. C263

Fig. C264

Fig. C265

Fig. C266

Fig. C267

Fig. C268

Fig. C269

Fig. C270

Fig. C271

Fig. C272

Fig. C273

Fig. C274

Fig. C275

Fig. C276

Fig. C277

Fig. C278

Fig. C279

Fig. C280

Fig. C281

Fig. C282

Fig. C283

Fig. C284

The Ear.

Fig. C285

Fig. C286

Fig. C287

Fig. C288

Fig. C289

Fig. C290

Fig. C291

Fig. C292

Fig. C293

Fig. C294

Fig. C295

Fig. C296

Fig. C297

Fig. C298

Fig. C299

Fig. C300

Fig. C301

Fig. C302

Fig. C303

Fig. C304

Fig. C305

Fig. C306

Fig. C307

Fig. C308

Fig. C309

Fig. C310

Fig. C311

Fig. C312

Fig. C313

Fig. C314

Fig. C315

Fig. C316

Fig. C317

Fig. C318

Fig. C319

Fig. C320

Fig. C321

Fig. C322

Fig. C323

Fig. C324

Fig. C325

Fig. C326

Fig. C327

Fig. C328

Fig. C329

Fig. C330

Fig. C331

Fig. C332

Fig. C333

Fig. C334

Fig. C335

Fig. C336

Fig. C337

Fig. C338

Fig. C339

The Integument.

Fig. C340

Fig. C341

Fig. C342

Fig. C343

Fig. C344

Fig. C345

Fig. C346

Fig. C347

Fig. C348

Fig. C349

Fig. C350

Fig. C351

Fig. C352

Fig. C353

Lymphatic System.

Fig. C354

Fig. C355

Fig. C356

Fig. C357

Fig. C358

Fig. C359

Fig. C360

Fig. C361

Textbook Table of Contents

I have endeavored in this work to produce an Atlas that will serve the practical needs of students of medicine and practicing physicians. It is not intended to be an Atlas for the use of experts in Anatomy. Consequently in the make-up of the book a limitation to what was absolutely necessary seemed to me a prime consideration.

In its outward form this first volume of the work is treated throughout as an Atlas, is arranged primarily for use by classes in dissection and follows closely the usual methods employed in such classes. Any difficulty that might arise for the beginner by an unusual method of presentation of the figures has, therefore, been carefully avoided.

The illustrations are so arranged that there is to be found on the opposite page, in addition to the explanation of the figures, a brief descriptive text. This enables the student using the book during his dissection to review rapidly the chief points in his preparation. In the Myology the explanatory text takes the form of tables which give at a glance the origin, insertion, nerve supply and action of the muscles. As regards the methods of reproduction of the figures, polychromatic lithography is used for the first time - so far as I am aware - in anatomical illustrations. Of the 34 colored plates 30 are reproduced by this process, the remaining 4 by the method of three (four)- color printing, again used for the first time in this connection. Nearly all the figures in the Myology are reproduced in this manner. For the other illustrations the so-called autotype process is used, and its suitability for the purpose may be seen from the Atlas itself. In addition key-figures, diagrams, etc. have been reproduced by line etching.

For greater convenience special colors have been extensively used in the illustrations reproduced by the autotype process, a chamois tint for the bones in illustrations of the articulations and many of the muscle figures, different colors for the individual skull bones in representations of the entire skull and in topographic figures of the skull bones. For the names of parts the Basel Nomenclature has been used.

The publishers have spared no pains in producing a book that certainly surpasses in excellence of reproduction all previous works, while at the same time it does not materially fall behind the most of them in the number of illustrations.

Würzburg, October 1903.

The Author.

The second edition of the first volume shows very important changes. In the first place the former lithographed plates of the Myology have been entirely omitted and replaced by polychromatic autotypes, as had already been done in the second and third volumes of the first edition. This was done partly for uniformity in reproduction, partly because the illustrations of the first volume were not pleasing to many readers on account of the colors being too bright and glaring on the white paper. I have especially decided to provide new illustrations of the muscles, since those of the first edition frequently did not give a sufficiently natural impression owing to the position of the cadaver. Instead of using photographs of the cadaver, those of an athletic man of small stature were taken as a foundation. These photographs were prepared by the illustrator Mr. K. Hajek and within outlines prepared from them the muscles were drawn from dissections. In this way one obtains correct and expressive figures which, furthermore, are more in keeping with the format of the book. The use of yellow, red and blue colors is naturally merely conventional, although they approximate the natural tints. At the same time the number of the illustrations for the Myology was considerably increased and, furthermore, for the trunk, and especially the thorax and abdomen three-quarter views were employed instead of complete profiles. Mr. K. Hajek has drawn the illustrations in a thoroughly satisfactory manner.

The portions of the book dealing with the Osteology and Syndesmology have also been expanded in various places.

Würzburg, July 1913.

The Author.

Unlike the earlier editions the seventh and eighth have undergone some not unimportant changes. Some Röntgen figures from Grashey's Atlas have been included, new figures of the muscles of the neck and face replace the older ones and a number of the osteological figures have been renewed. In correspondence with these changes the text has been somewhat enlarged.

Bonn, November 1929 and February 1932.

The Author.

This first volume of the second Englished edition of Sobotta's Atlas of Descriptive Anatomy is translated and edited from the sixth German edition. Compared with the first Englished edition there are a number of differences, the chief one being that the text-book feature has disappeared, the book being more strictly an anatomical Atlas. The descriptions of the structures shown in the illustrations are greatly condensed and, as far as possible, are on the pages facing the illustrations under consideration. The labels on the figures are the B. N. A. terms in their original Latin form; in the text, however, it has seemed advisable to translate them, for the most part, into their English equivalents or, in rare cases, to use a term more familiar to English-speaking students. Where misunderstandings might occur the B.N.A. term in also given.

The text, however, is relatively unimportant; the illustrations are the chief glory of the book and to give these English explanations and to render them available for English-speaking students of anatomy is the object of this edition.

The Editor.

This second volume of the Atlas of Descriptive Anatomy treats of the anatomy of the viscera including the heart. It has seemed advantageous to include the heart since in dissection it is usually considered with the other viscera of the thorax.

The choice of preparations for illustration and their manner of representation follow the plan used in the first volume, the object being to present them from the standpoint of topographic anatomy.

Würzburg, August 1904.

The Author.

In this second edition a series of changes have been made in that the lithographic plates have been replaced by others, reproduced partly by so-called three-color printing partly by polychrome autotype printing. In so doing some plates were greatly altered and especially for the situs of the abdominal viscera and the peritoneum and partly for the female genitalia new figures have been added. All the figures are from the skilled hand of K. Hajek.

Würzburg, February 1914.

The Author.

In contrast to the third, fourth and fifth editions, which were essentially the same as the second, this sixth edition presents a number of new illustrations, especially of the stomach, intestines, liver, lungs and pericardium.

Bonn, November 1927.

The Author.

In this seventh edition all colored figures have been reproduced by the same method, i.e. by the polychromatic autotype process. Some additions have been made, of which there may be especially mentioned a series of new figures (mouth cavity, accessory cavities of the nose, thoracic viscera, conducting bundles of the heart). Further, some of the figures have been replaced by new ones.

Bonn, June 1931.

The Author.

An experience with the work of the Anatomical Laboratory, extending over many years, has convinced the author of the advisability of presenting illustrations of the peripheral nervous system and of the blood vessels as they are seen by the student in his dissections, i.e. the nerves and arteries of any region in the same figure. Consequently in the majority of the figures representing these structures arteries and nerves, arteries, veins and nerves, or arteries and veins are shown in each figure, and only occasionally is there a departure from this plan, when, for the sake of clearness, accessory figures showing only the arteries or the nerves (for example, the cranial nerves) are added.

This method of arrangement has the advantage for the student, that he finds on a single page of the Atlas representations of all the structures he has seen at any one stage of his dissection, and is not obliged to waste time in turning from page to page of the Volume. Each figure is one of a series of topographic anatomical illustrations.

The simultaneous representation of blood vessels and nerves makes reproduction in colors necessary. The arteries are shown red, the veins blue and the nerves yellow. For the reproduction in color autotypes have been used, prepared in a most satisfactory matter by Messers. Angerer and Göschl of Vienna and the various plates have at the same time been adapted for the coloration of the other tissues shown (muscles, bones, fat, skin etc.). In this way colored illustrations have been obtained, which do not, it is true, show an absolutely natural coloration, but nevertheless approximate it sufficiently to give an extraordinarily accurate general impression. All the figures of the Volume are from originals by K. Hajek, whose artistic talent and skill in anatomical illustrations are again fully manifested.

As was stated in the Preface to the first Volume, the endeavor has been to make of the Atlas a work that would be of use to students and practitioners, not one intended for expert Anatomists. Whoever wishes information in special fields of anatomy, will necessarily turn to special treatises on those fields, and this Atlas, even were it twice as extensive, would not be sufficient for him. On the other hand an undue expansion of the book and overloading it with illustrations of interest only to specialists, would only render it more difficult for the student or practitioner to get the information he desires. The chief object has therefore been to limit the illustrations to the necessities of the case, but to present these in a series of comprehensive figures, showing step by step the stages usually followed in dissection.

In correspondence with the arrangement followed in the first and second volumes, this one presents alternately pages of text and figures. The latter show the principal figures of the Atlas, the former, in addition to accessory and schematic figures and the explanations of the chief figures, a brief text intended for review during the use of the Atlas in the dissecting room, this being accompanied by references to other illustrations in the volume where the structures under consideration are shown.

Würzburg, May 1906.

The Author.

The Second Edition of this Atlas differs from the first by an increase in the number of illustrations. For the brain, especially, and for the sense-organs a number of new figures have been added. The representation of the principal fibre tracts has been extensively altered and in this connection some of the schematic figures have been replaced by new ones. In addition a considerable number of schemata have been added, which have in many cases been adapted from the admirable figures by Villiger.

The alphabetical index at the end of the Volume refers to the figures. In the text brief references are given to pages on which further statements as to the structures under consideration are to be found, and a special page reference was therefore unnecessary.

Würzburg, Spring, 1915.

The Author.

In contrast to the third, fourth and fifth editions, which were essentially the same as the second, this sixth edition presents a number of new illustrations, especially of the nerves and vessels of the lower limb, of the brain, the eye and the auditory organ.

Bonn, 1927.

The Author.

This seventh edition, compared with the sixth, has been improved, apart from lesser modifications, by the addition of three large, full-page, colored representations of the cranial, cervical and thoracic portions of the sympathetic nervous system, taken, by kind permission, from the admirable publications of Mr. Braeucker of Hamburg.

Bonn, November 1930.

The Author.

The eighth edition differs but little from the seventh, but contains some new illustrations of the blood vessels (and nerves), especially those of the posterior abdominal wall; and of the lymphatic vessels. Further the structure of the medulla oblongata, the pons and the corpora quadrigemina is shown in some schemata taken from the diagrams of Müller-Spatz, published by the J. F. Lehmann's Verlag.

Bonn, March 1933.

The Author.

Explanation of the abbreviations used in the illustrations.

Abbreviations not listed may be determined by the context.

X after a name denotes that the part indicated has been cut away or cut through.

( ) denotes that the part is seen through another structure. In the case of the facial muscles, however, ( ) denotes the proposed new nomenclature.

1, 2, 3, etc. after a term indicates that the part concerned is shown in different parts of its course.

If a part is not named, as a rule it has already been named on the preceding figure.

For the structure of bone see here.

The skeleton of the trunk consists of the vertebral column together with the ribs and sternum.

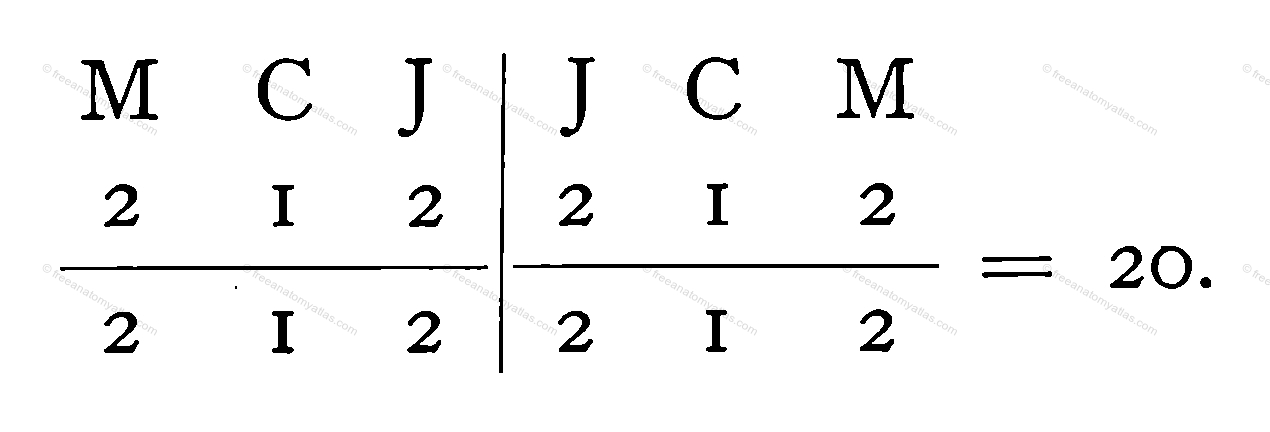

True and False Vertebrae may be distinguished. The former are represented by 7 cervical vertebrae, 12 thoracic and 5 lumbar, while the latter are two composite bones, the sacrum and coccyx.

The essential parts of a vertebra are the body (corpus), the arch (arcus), the transverse processes, the spinous process and the articular processes.

The body (Corpus) forms the principal part of the vertebra; it lies anteriorly and has a low cylindrical form. From it arises by means of the pedicles (radices) the arch (arcus), between which and the posterior surface of the body is the vertebral foramen, usually more or less transversely elliptical in form: Each pedicle (radix) presents an upper shallower and a lower deeper notch (incisura vertebralis). When the vertebrae are articulated the notches of successive vertebrae form foramina (foramina intervertebralia) through which the spinal nerves pass. Those vertebrae with which ribs articulate present toward the posterior part of both the upper and lower border of the body on each side an articular surface (fovea costalis superior and inferior) for the head of the rib.

The transverse processes are paired processes that project laterally from the anterior part of the arch or, in the case of the cervical vertebrae, from the pedicles. Their extremities, in the case of the thoracic vertebrae, present on their anterior surface an articular surface (fovea costalis transversalis) for the tubercle of the rib.

The unpaired, median spinous process arises from the posterior part of the arch and is directed backwards or backwards and downwards. The portion of the arch between the spinous and transverse process on each side is termed the lamina.

The paired articular processes serve for the articulation of the vertebrae with one another. Each vertebra bears two superior and two inferior articular processes. They arise from the arch close behind the pedicles and bear articular surfaces, which lie in different planes in different vertebrae.

The Cervical Vertebrae have small, transversely elliptical bodies, the upper concave surface of each overlapping laterally the lower convex surface of the vertebra next above. The arches are of moderate height and the vertebral foramen relatively large, especially in its transverse diameter, and of a rounded triangular form. The articulating processes have their almost flat surfaces situated obliquely in a plane intermediate between the frontal and the horizontal. The transverse processes enclose a foramen (foramen transversarium), the anterior portion of each process representing a rudimentary rib fused with the body and transverse process. The rib element of the seventh vertebra occasionally remains separate, forming a cervical rib. Each transverse process presents on its upper surface a groove for the spinal nerve (sulcus nervi spinalis), which extends from the vertebral foramen over the foramen transversarium to the tip of the process, where it separates an anterior from a posterior tubercle. This is due to the origin of the transverse processes from the pedicles, whence they lie in the regions of the vertebral incisures. The spinous processes are short and bifid at their tips; they are almost horizontal or only slightly inclined except that of the seventh vertebra (vertebra prominens), which inclines downwards like those of the thoracic vertebrae and is never bifid, resembling the spinous processes of the thoracic vertebrae rather than those of the other cervicals. On account of its long spinous process the seventh (vertebra prominens) is the first vertebra that can be felt in the living body. Furthermore its foramen transversarium is small. It is a typical cervical vertebra, presenting, however, characters transitional to those of the thoracic series.

The atlas and axis (epistropheus) are on the contrary atypical vertebrae. The atlas has no body. Instead there is both an anterior and a posterior arch. The vertebral incisures and the spinous process are also lacking. In place of the latter there is a posterior tubercle and opposite this on the anterior surface of the anterior arch there is ani anterior tubercle. In the place of the lacking articular processes there are articulating surfaces on the upper and under surfaces of what are termed the lateral masses of the bone. The large transverse processes have a foramen transversarium, but no tubercles and no groove for the spinal nerve. The posterior arch is low; on the posterior surface of the anterior arch is a roundish, slightly concave articular surface for the odontoid process (dens) of the axis (epistropheus). The vertebral foramen is very large and consists of a smaller anterior and a larger posterior portion; it is bounded laterally by the prominent lateral masses. Over the upper surface of the posterior arch there runs a shallow groove (sulcus arteriae vertebralis) for the vertebral artery; occasionally it becomes deeper or is even converted into a canal.

The axis (epistropheus) possesses a conical process, the odontoid process (dens) arising from its body. Upon this process there is an anterior and usually a posterior articular surface. The upper articular processes are replaced by articulating surfaces and the superior vertebral incisure is wanting. The transverse processes are very small; there are no tubercles and no groove for the spinal nerve. The spinous process is especially strong and bifid and it, as we)l as the under surface of the bone, resembles the corresponding part of typical cervical vertebrae.

The thoracic vertebrae have moderately large bodies which increase both in height and depth from above downwards. The surfaces of the bodies are flat and heart-shaped. The vertebral foramen is absolutely and relatively small and almost circular. On the posterior part of both the upper and lower borders of the lateral surfaces of the body are articular facets (fovea costalis superior and inferior) which, with the corresponding half facets of adjacent vertebrae, form the articular surfaces for the heads of the ribs. The articular processes have nearly flat surfaces which lie almost in the frontal plane; the lower ones hardly project beyond the surface of the arches. The transverse processes are strong, directed laterally and distinctly backward and bear upon the anterior surfaces of their thickened, free ends articular surfaces for the tubercles of the ribs (foveae costales transversales).

The spinous processes are very strong, triangular, thickened at their ends and directed distinctly downwards; those of the middle thoracic vertebrae overlap each other like the shingles on a roof.

The first thoracic vertebra has on each side a complete fovea for the first rib and a half fovea for the second rib, that is to say one and one half instead of two half foveae. The last two thoracic vertebrae have on each side a complete fovea, each articulating with only one rib. The eleventh and especially the twelfth thoracic vertebrae form a gradual transition to the lumbar vertebrae, since the spinous processes are directed straight backwards and are laterally compressed, the foveae costales transversales are lacking and, associated with a rudimentary condition of the transverse processes, accessory and mamillary processes may occur (12 Thoracic). Also the articular surfaces and the lower articulating processes of the twelfth thoracic vertebra are already sagittal in position.

The lumbar vertebrae are the largest of all the true vertebrae. They have high and broad bodies with flat, bean-shaped (that is to say, the contact surface for the adjacent vertebra is elliptical, but somewhat concave posteriorly) not quite parallel surfaces (the surfaces are not parallel because the lumbar portion of the vertebral column is strongly convex forwards, the vertebral bodies being noticeably higher in front than behind), as well as high and strong arches with very strong processes. The anterior as well as the lateral surfaces of the bodies are hollowed out (consequently the contact surfaces are larger than the transverse section through the middle of the bodies). In size these vertebrae increase continuously and quite distinctly from the first to the fifth. The vertebral foramen is narrow and rounded triangular. The surfaces of the articular processes stand almost in the sagittal plane; they are distinctly curved, the superior processes being concave and directed medially while the inferior are convex and directed laterally.

The upper articular processes bear on their upper margins a rounded tubercle, the mamillary process. The transverse processes are long, flat, rib-like and directed almost exactly laterally. At the base of each is a sharp process directed backwards, the accessory process, which corresponds to the tip of the transverse process of a thoracic vertebra, the main portion of a transverse process corresponding to a rib fused with the vertebra. The spinous processes are strongly compressed laterally, are directed almost exactly backwards and are slightly thickened at their ends.

The sacrum is a curved, shovel-shaped bone, broader above and narrower below. Its posterior surface (facies dorsalis) is convex and roughened, the anterior surface (facies pelvina) is concave and relatively smooth, the broader upper surface is termed the base and the lower more pointed end the apex.

The dorsal surface presents a rough median ridge or crest, which in many cases is frequently interrupted. It is formed by the fusion of the spinous processes of five sacral vertebrae. In addition to this unpaired median crest there are on the dorsal surface on each side two lateral, rarely continuous ridges, which are separated by four foramina, the posterior sacral foramina. Medial to these foramina lies the sacral articular crest formed by the fusion of the articular processes and lateral is a crest (crista sacral is lateralis) formed by the fusion of the transverse processes. The upper articular process of the first sacral vertebra remains distinct for articulation with the last lumbar vertebra, while the lower process of the last sacral vertebra forms a process, the sacral cornu, for articulation with the coccyx (but without an articular surface). The two sacral cornua bound the lower opening (hiatus sacralis) of the canal contained within the sacrum (canalis sacralis).

The pelvic surface presents four pairs of anterior sacral foramina corresponding to but larger than the four posterior foramina. Extending between the foramina of each pair is a low, rough ridge (linea transversa), which indicates the boundary between the bodies of two fused sacral vertebrae. The anterior foramina diminish in size from above downwards.

The apex of the sacrum appears as if cut off and possesses a small elliptical surface to which the coccyx is apposed.

The base shows a surface corresponding with the under surface of the last lumbar vertebra, with which it articulates. Between this bean-shaped surface and the superior articular process is a superior vertebral incisure, which, with the inferior incisure of the last lumbar vertebra, forms the last intervertebral foramen. Behind the surface for the last lumbar vertebra lies the upper end of the sacral canal and laterally are the lateral masses. The base of the sacrum is separated from the concave pelvic surface by a feeble line, which is the sacral part of the linea terminalis (see here).

In a lateral view of the sacrum one sees the articulating surface of the lateral mass, which serves for articulation on each side with the innominate bone and through this for the completion of the pelvic limb-girdle. It is formed anteriorly by an uneven, ear-shaped auricular surface, which is covered with cartilage, and posteriorly by a rough, depressed area, the sacral tuberosity, which is not covered by cartilage. Below this the lateral surface of the bone, which is fairly broad above, becomes exceedingly narrow; i.e. the bone which is relatively thick at the base now becomes quite thin.

The sacral canal, the continuation of the vertebral canal, traverses the entire length of the sacrum. Posteriorly it is bounded by a flattened bony mass formed by the fused arches of the sacrum, which bear the medial sacral crest. The canal opens in front and behind into the sacral foramina by means of the intervertebral foramina, which, in the sacrum, in contrast to the true vertebrae, are contained within the bone and consist of short canals. The posterior wall of the sacral canal does not extend to the apex of the bone, but terminates at about the boundary between the fourth and fifth sacral vertebrae. There is thus formed the hiatus of the sacral canal (see here).

The Coccyx is a small bone formed by the fusion of four or five rudimentary coccygeal vertebrae. The first of these vertebrae possesses two upwardly projecting cornua which are the rudiments of articular processes and serve for articulation with the sacrum. Furthermore, this same vertebra has feebly developed transverse processes. The upper end of the coccyx unites with the apex of the sacrum.

The second to the fifth (sixth) coccygeal vertebrae represent merely the bodies of these vertebrae and are usually irregular in shape, mostly flattened spherical. The individual coccygeal vertebrae are either united with one another by synchondroses or have a bony union (synostosis).

The vertebral column is a bony column with several curvatures and is composed of 26 separate bones, i.e. 24 true vertebrae, the sacrum and the coccyx. Its curvatures are as follows: One in the cervical region slightly convex anteriorly, one in the thoracic region strongly concave anteriorly, one in the lumbar region strongly convex anteriorly and one in the sacral and coccygeal regions strongly concave anteriorly. The transition from the lumbar convexity to the sacral concavity is somewhat abrupt; the region of the last intervertebral disc is termed the promontary.

The width of the column is greatest at the upper part of the sacrum; from this level the vertebrae become gradually smaller toward the coccyx and also upwards toward the middle of the thoracic region. From there upwards the vertebrae again broaden to the upper thoracic and lower cervical regions, diminishing again up to the axis (epistropheus), while the atlas, with its strongly developed transverse processes, is again notably broader. The greatest thickness of the column is in the lumbar region.

The bodies of the vertebrae are not in actual contact with one another, but are joined together by intervertebral discs. On the other hand the articular processes are in immediate contact by their articular surfaces. Each adjacent pair of vertebral incisures form an intervertebral foramen; the uppermost pair of these lies between the second and third cervical vertebrae and the lowest pair between the fifth lumbar vertebra and the sacrum, so that there are altogether 23 pairs of foramina. They are largest in the lumbar region and smallest in the thoracic. In the cervical region the foramina lie in the intervals between the transverse processes, in the thoracic and lumbar regions they are anterior to these processes.

The intervertebral foramina lead into the vertebral canal, which represents the sum of the separate vertebral foramina and is an almost cylindrical cavity that begins at the atlas and is continued below into the sacral canal (see here).

The ribs (costae) are long flat bones and may be regarded as consisting of a bony rib and a costal cartilage,. In the bony rib there may be noted a rounded enlargement at the posterior, vertebral end, the head (capitulum), with an articular surface for articulation with the vertebral bodies. This surface, at least in the ribs that articulate with the bodies of two vertebrae, is divided into two portions by the capitular crest. On the head there follows a distinct constriction of the rib, the neck (collum), whose upper border is provided with a ridge (crista colli) that gradually fades out on the body of the rib. Where the neck passes over into the body of the rib there is a rough tubercle bearing an articular surface for articulation with the transverse process of a thoracic vertebra.

The body (corpus) of the rib forms the principal part of the bony rib. It is a long, flat, vertically placed bone curved in correspondence with the curvature of the thorax. Near the tubercle it presents a rough surface, the angle of the rib, and at this point the rib, which at first was directed somewhat backwards, bends anteriorly. At the lower border, or more exactly, on the inner surface of the body, is a groove (sulcus costae), which gradually fades out toward the anterior end of the rib. This is slightly hollowed out for the reception of the costal cartilage.

The third to the tenth bony ribs have a typical form. The first and second and the eleventh and twelfth are atypical.

The first rib is short and broad. It is not placed vertically, but almost horizontally and its surfaces are directed upwards and somewhat outwards, and downwards and somewhat inwards. As a rule it has no capitular crest and no angle. On its upper surface, not far from where it joins its costal cartilage, there is a distinctly roughened area, the scalene tubercle for the insertion of the Scalenus anterior, and behind this a slight furrow, the subclavian groove for the subclavian artery. Behind this again is a rough surface for the insertion of the Scalenus medius. The neck of the first rib is long and thin.

The second rib is markedly longer and smaller than the first. Its posterior part is similar to that of the first, one surface looking upward and outward and the other downward and inward, but its anterior part is placed nearly vertical, as in the typical ribs. The angle and the tubercle coincide, but on the other hand there is a capitular crest. At about the middle of the length of the rib its lateral surface shows a roughened area, the tuberosity, for the insertion of a serration of the Serratus anterior.

The eleventh and twelfth ribs are quite rudimentary. They possess only a head, which however has no capitular crest. The tubercle is usually wanting on the eleventh rib and frequently the angle; on the twelfth rib also both are wanting. In both the costal sulcus is absent. The twelfth rib is often very short and it varies greatly in length.

The sternum is a flat, elongated bone in which three parts may be recognized, a manubrium, a body (corpus) and a xiphoid process.

The manubrium is the upper, broadest, slightly curved portion of the sternum and is separated from the body of the bone by the sternal synchondrosis. There may be distinguished on the manubrium an upper, shallow depression, the jugular notch or incisure, lateral to which on the two upper angles of the bone are two lateral, stronger depressions, the clavicular incisures, for the reception of the sternal ends of the clavicles. Immediately below these lie two broad shallow depressions, the first costal incisures, for the attachment of the cartilage of the first rib. At the lower end of the manubrium there is on either side a half incisure for the second rib.

The body (corpus) of the sternum is narrower and thinner but longer than the manubrium. For the most part it broadens from above downwards. It unites with the manubrium at a very obtuse angle, the sternal angle, which is not always very distinct. Its anterior surface is termed the sternal plane. The lateral borders show incisures for the reception of the second to the seventh costal cartilages. Frequently low transverse ridges upon the anterior surface of the bone unite the incisures of the two sides (see Fig. A39). Only the lower half of the incisure for the cartilage of the second rib is found on the body of the sternum, the incisures for the fifth to the seventh lie close to one another, while those for the second to the fifth rib are placed at quite distinct intervals. That for the seventh rib is in the angle between the body and the xiphoid process.

The xiphoid process is usually only partly bony, being usually cartilaginous in its lower part. It is often perforated or cleft below and is especially variable in form. Its upper bony portion usually fuses with the body of the sternum in advancing years.

The thorax is formed by the twelve thoracic vertebrae, the twelve pairs of ribs and the sternum.

The ribs increase in length from the first to the seventh and then diminish rapidly. The costal cartilages of the uppermost and lower-most ribs are the shortest.

The seven upper ribs which are attached by their cartilages directly to the sternum are termed the true ribs (costae verae), in contrast to the five lower ones, the false ribs (costae spuriae), which are attached to the sternum only through the intervention of the seventh costal cartilage, or, as in the case of the eleventh and twelfth ribs, have no connection with the other ribs or with each other (floating ribs). The cartilages of the sixth (in some cases even of the fifth) to the tenth rib are united with one another by upwardly and downwardly directed processes and form the costal arch. The union may be a synchondrotic one or else diarthrotic. In the region of the costal arch the cartilages are frequently greatly broadened. They always diminish in breadth from their outer ends towards the sternum. Not infrequently the middle ribs especially form what is termed a costal window, a rib dividing, usually in its bony portion, and then uniting again in the neighbourhood of the cartilage. The eleventh and twelfth ribs have only cartilaginous tips, which are very short and end freely.

The ribs, which form the principal part of the thoracic wall, are so placed that between each two ribs there is an interspace, the intercostal space, which is considerably wider than the rib itself. There are eleven of these spaces on each side. The last is very short and, like the next to the last, is open anteriorly.

The first and second costal cartilages slope slightly downwards toward the sternum, the third to the fifth are almost horizontal, while from the sixth downwards the cartilages are directed sharply upwards, especially in expiration, during which a distinct angle is developed at the junction of the bony rib with its cartilage, an angle which is almost completely obliterated during inspiration.

The sternum with the costal cartilages and the adjacent portions of the bony ribs forms the anterior wall of the thorax. It does not lie exactly in the frontal plane, but its upper end is directed somewhat backwards and is therefore somewhat nearer the vertebral column than is the lower part. The greater distance of the lower part from the column is mainly due to the strong concavity of the thoracic portion of the column.

The anterior wall of the thorax is markedly shorter than the posterior, since the upper border of the manubrium sterni corresponds to the interval between the second and third thoracic vertebrae in the neutral position, being lower during expiration and higher in inspiration. The tip of the xiphoid process lies at the level of the ninth thoracic vertebra, or, in accordance with its variable length, occasionally at that of the eighth or tenth.

The posterior wall of the thorax is formed by the twelve thoracic vertebrae and the posterior portions of the twelve pair of ribs. Since the bodies of the former project strongly into the thoracic cavity there is a deep groove on each side of the vertebral column, the pulmonary groove (sulcus pulmonalis).

The lateral wall of the thorax is formed by the bony ribs. It is longer posteriorly than in front, where the eleventh and twelfth ribs are lacking, and during expiration reaches, opposite the twelfth rib, the level of the second lumbar vertebra.

The walls of the thorax enclose the thoracic cavity, which is almost conical in shape, the apex being directed upwards. This cavity has an upper and a lower aperture, the upper one being markedly smaller than the lower. It is bounded by the first thoracic vertebra, the first rib and the upper border of the manubrium sterni. The much larger lower aperture is bounded by the twelfth thoracic vertebra, the twelfth, eleventh and tenth ribs, the costal arch and the xiphoid process. The angle that the costal arch forms with the xiphoid process is known as the infrasternal angle.

In transverse section the thoracic cavity is heart-shaped or kidney-shaped on account of the manner in which the bodies of the vertebrae project into it. As a result the sagittal diameter of the thorax is small, much smaller than the transverse, especially in the upper part.

The bones of the head taken together form what is termed the skull (cranium). Two groups of skull bones are usually recognized, the bones of the cranium and the bones of the face. To the former belong the occipital, the sphenoid, the temporals, the parietals, the frontal and the ethmoid.

The bones of the face are the nasals, the lacrimals, the vomer, the inferior concha, the maxillae, the palatines, the zygomatics, the mandible and the hyoid.

In the occipital bone the following parts may be distinguished:

The basilar portion lies in front of the foramen magnum, the lateral portions form the lateral boundaries of this and the squamous portion lies behind it.

The basilar portion in the skull of the adult is continuous at its anterior end with the body of the sphenoid. It presents a horizontal, roughened, lower surface, which has in the median line a tubercle, the pharyngeal tubercle. Its upper or cerebral surface is concave. This latter surface forms the larger and posterior part of the clivus and shows a shallow groove at the margin of the petro-occipital fissure, the inferior petrosal groove.

The lateral portions bear upon their under surfaces the elongated, convex occipital condyles and pass without any sharp boundary into the basilar portion anteriorly and the squamous portion posteriorly. Behind the condyles is a shallow depression, the condyloid fossa, in which a short condyloid canal usually opens. When this canal is present its inner opening is on or near a broad groove, the sigmoid sulcus (Fig. A56). This, on the cerebral surface of the lateral portion, arches around the jugular process, beginning at the jugular notch, which, together with a similar notch on the temporal bone forms the jugular foramen. A small projection (intrajugular process) on each of these two bones divides the foramen into a small anterior (medial) and a larger posterior (lateral) portion (Fig. A55). The jugular process projects strongly laterally and serves for the articulation of the lateral portion of the occipital with the pyramid of the temporal bone. Medial to the jugular process. There is on the cerebral surface of the lateral portion a rounded elevation, the jugular tubercle (Fig. A56). Between this and the condyle there passes almost transversely through the bone the hypoglossal canal for the nerve of that name.

The squamous portion is by far the largest portion of the occipital bone. It is rather flat but is curved like a shovel, being concave on the inner surface and convex on the outer. It is typically triangular. Along the occipito-mastoid suture it articulates with the mastoid portion of the temporal bone and at the lambdoid suture with the two parietal bones. The upper angle abuts in the middle of the lambdoid suture upon the posterior end of the sagittal suture. Its cerebral surface presents a cross-like figure, whose upper and lateral arms are formed by grooves, while the lower arm is formed by a ridge, the internal occipital crest, which passes toward the posterior border of the foramen magnum. The groove forming the upper arm of the cross is the lower portion of the sagittal sulcus, while the transverse grooves are the transverse sulci; the similarly named blood sinuses of the dura mater occupy these sulci. The central point of the cross-like figure is the internal occipital protuberance. The arms of the cross-like figure separate two shallow superior occipital fossae from one another and from two deeper inferior occipital fossae.

The outer surface of the squamous portion of the occipital is divided into two parts by the superior nuchal lines, which pass laterally from the external occipital protuberance. The upper, triangular, relatively smooth part is the occipital surface, the lower rough part the nuchal surface. Above the superior nuchal lines there are usually two arched supreme nuchal lines. From the external occipital protuberance the external occipital crest extends downwards toward the posterior border of the foramen magnum, and from about its middle the inferior nuchal lines curve outwards, parallel to the superior ones.

The sphenoid bone has an unpaired body (corpus), two great wings (alae magnae), two lesser wings (alae parvae) and two pterygoid processes.

The body (corpus) unites in later life by its posterior surface with the basilar portion of the occipital. It contains a cavity filled with air, the sphenoidal sinus, which is divided into two parts by a septum and communicates by two apertures with the posterior part of the nasal cavity. The septum shows itself on the anterior surface of the body as the sphenoidal crest. The anterior wall is formed by two thin bony plates, the sphenoidal conchae, which originally belong to and are often united with the ethmoid bone. The sphenoidal crest is continued upon the under surface of the body as the rostrum and serves for articulation with the wings of the vomer. The upper surface of the body is partly formed by the sella turcica, in front of which is a flat surface, which posteriorly bounds the sulcus chiasmatis of the sella turcica and anteriorly projects towards the lamina cribrosa as the ethmoidal spine. The posterior boundary of the sella turcica is the dorsum sellae with the two posterior clinoid processes at its outer ends; in front of it is the deepest part of the sella, the hypophyseal fossa, which is bounded in front by the tuberculum sellae (Fig. A48). In front of the tuberculum sellae there is a shallow, transverse groove, the sulcus chiasmatis. From the lateral parts of the tuberculum sellae the short middle clinoid processes project. At the sides of the hypophyseal fossa and on the root of the great wing there is a shallow, but broad, longitudinal groove, the carotid groove, for the internal carotid artery. It is bounded laterally by a small bony plate, the sphenoidal lingula (Fig. A48). The anterior part of the clivus, behind the dorsum sellae, belongs to the sphenoid bone (Fig. A48).

The lesser wings (alae parvae) are small horizontal plates of bone which arise from the lateral surfaces of the body of the sphenoid, each by two roots which enclose the optic foramen. Their anterior borders articulate with the orbital portion of the frontal bone in the spheno-frontal suture; their posterior sharper borders form a boundary for the anterior and middle cranial fossae and end medially, toward the sella turcica, in sharp hook-like points, the anterior clinoid processes. The lesser and greater wings are completely separated by the superior orbital fissures.

The great wing (ala magna) arises from the lateral surface of the body of the sphenoid. In its root there are three foramina, the foramen rotundum directed obliquely forward and leading into the pterygopalatine fossa, the elliptical foramen ovale also placed obliquely and the small, round foramen spinosum. The great wing has three principal surfaces, cerebral, temporal and orbital, and the following borders, a squamous border (margo squamosus) for the squamous portion of the temporal, a frontal border (margo frontalis) for the orbital portion of the frontal, a zygomatic border (margo zygomaticus) for the zygomatic and a parietal angle for the parietal. The lateral posterior process which bears the external opening of the foramen spinosum and is directed toward the under surface of the pyramid of the temporal bone is termed the spine of the sphenoid (spina angularis). The cerebral surface is concave and, in addition to the three foramina, shows digitate impressions. The orbital surface is almost flat and forms a part of the lateral wall of the orbit. A sharp orbital crest separates it from the small spheno-maxillary surface. Similarly the temporal surface is divided by the infratemporal crest into the upper temporal and the lower infratemporal surfaces, the latter, again, passing into the spheno-maxillary surface, there being frequently between the two a sphenomaxillary crest. The infratemporal surface bears the external openings of the foramen ovale and foramen spinosum, the spheno-maxillary surface that of the foramen rotundum.

The pterygoid processes extend almost vertically downwards, almost parallel with one another, from the under surface of the body of the sphenoid; they arise on each side by two roots which enclose between them the pterygoid(Vidian) canal, which is directed almost horizontally in the sagittal plane. It unites the foramen lacerum with the pterygo-palatine fossa. Below, the pterygoid processes divide into a smaller inner and a broader outer plate (lamina) separated in their upper part by a groove, the pterygoid fossa, in their lower part by a cleft, the pterygoid fissure, which is filled by the pyramidal process of the palatine bone. The inner plate has at its base an elongated shallow depression, the scaphoid fossa, and at its lower end and separated from it by a groove, the hamulus. A small process projecting toward the body of the sphenoid, the processus vaginalis, encloses the pharyngeal canal by uniting with a process of the palatine bone. From the scaphoid fossa a shallow groove, sulcus tubae auditivae extends toward the spinous process along the spheno-petrous suture. On the anterior surface of the pterygoid process is a groove, the pterygo-palatine groove, extending downwards from the anterior opening of the pterygoid canal. It forms with the corresponding grooves on the palatine bone and maxilla the pterygo-palatine canal.

The temporal bone has four parts:

These four parts group themselves around the external auditory opening, in such a way that the squamous part lies above it, the mastoid part behind, the tympanic part below and anterior, and the petrous part medial and anterior.

The squamous portion (squama temporalis) articulates by a strongly curved, irregular border with the great wing of the sphenoid (margo sphenoidalis) and with the parietal (margo parietalis), the margins of the temporal bone overlapping those of the other hones in a squamous suture. Except for a small lower portion the squama is vertical in position and has an outer temporal and inner cerebral surface, the latter having ridges and depressions for the convolutions of the cerebral hemispheres and also grooves for the middle meningeal artery. It is more or less separated from the petrous portion by a petro-squamosal fissure, which tends to become obliterated in the adult. The temporal surface is smooth and presents a shallow groove for the middle temporal artery, beginning just above the external auditory opening. In addition there arises from the temporal surface the long zygomatic process, which articulates with the temporal process of the zygomatic bone. The process arises by a root from the vertical portion of the squama and by a second root from the small, lower, horizontal portion. Between the two roots lies the articular cavity for the head of the mandible (fossa mandibularis), in front of which is an articular tubercle, also partly covered with cartilage. The zygomatic process is at first almost horizontal, but later twists so as to lie in the sagittal plane. From its posterior extremity the hinder part of the temporal line passes upwards and backwards to be continued upon the parietal bone. Above the external auditory opening there is usually a sharp projection, the suprameatal spine.

The mastoid portion has as its chief part the large mastoid process, which forms the whole outer surface of this portion of the bone; it articulates by the parietal notch with the mastoid angle of the parietal and by its occipital margin with the squamous portion of the occipital (occipito-mastoid suture). It possesses a concave inner (cerebral) surface and a strongly convex roughened outer surface. The latter forms the broad, conical mastoid process which contains cavities filled with air, the mastoid cells, which communicate with the tympanic cavity. It gives attachment to several muscles and towards its posterior border has a deep groove (mastoid incisure) for the Digastric. Near the occipito-mastoid suture is a shallow groove for the occipital artery and the external opening of the mastoid foramen.

The principal part of the temporal bone, the petrous portion, is also termed the pyramid and is a three-sided pyramidal structure lying almost horizontally. In the adult only its three surfaces can be seen, the base being almost covered by the tympanic portion of the bone; in the new-born child and even somewhat later it is visible on the outer surface of the bone (Fig. A64, A65). The schematic sections (Fig. A66 and A67) show the arrangement of the four surfaces as well as the formation of the tympanic cavity and its continuation as the Eustachian tube (musculo-tubar canal) through the petrous and tympanic portions.

In the description that follows the parts of the bony labyrinth lying within the pyramid are not considered, nor is the tympanic cavity fully described. These parts will be described later (see here).

Two surfaces of the petrous portion, the anterior and the posterior, look toward the skull cavity; the third, inferior, is at the base of the skull, while the base (not labelled) forms the medial wall of the tympanic cavity. The three surface are separated by angles; the superior angle separates the anterior and posterior surfaces, the anterior separates the anterior and inferior and the posterior the posterior and inferior surfaces. The axis of the pyramid is oblique to the long axis of the skull passing from behind and lateral, anteriorly and medially. The apex of the pyramid lies at the foramen lacerum.

The anterior surface forms a portion of the middle fossa of the skull. It is separated by the petrosquamous fissure from the squamous portion of the bone, and bears a slight transverse elevation, the arcuate eminence, which is formed by the underlying semicircular canal.

Further towards the median line is a slit-like opening the hiatus of the facial canal, with a groove for the great superficial petrosal nerve extending toward the foramen lacerum.

Lateral and anterior to this is a second opening, the aperture of the superior tympanic canaliculus, with a similarly directed groove for the lesser superficial petrosal nerve. The part of the anterior surface of the pyramid that lies between the petro-squamous fissure and the arcuate eminence forms the roof of the tympanic cavity, the tegmen tympani. Near the apex of the pyramid is a very shallow trigeminal impression (see Fig. A48). The superior angle bears the superior petrosal groove and the anterior angle bounds the spheno-petrous fissure and the foramen lacerum. The posterior surface of the pyramid forms a part of the posterior cranial fossa. It presents a roundish opening, the internal auditory opening (porus acusticus internus), which leads into a canal, the meatus acusticus internus, running obliquely into the bone. Above this opening, immediately below the superior angle, is small depression, the subarcuate fossa, and lateral to the auditory opening there is a fissure-like opening, the external opening of the aquaeductus vestibuli, which lodges a portion of the internal ear. A shallow groove, the inferior petrosal sulcus, runs parallel to the posterior angle, being a continuation of the similarly named groove on the occipital bone. The apex of the pyramid has an opening with an irregular boundary, the internal carotid foramen (see below). Beside it, near the anterior angle of the pyramid, is the opening of a large canal, the Eustachian canal (canalis musculo-tubarius), which leads into the tympanic cavity.

The posterior angle is separated from the occipital bone by- the petro-occipital fissure and bears a shallow jugular notch, which, with the corresponding notch on the occipital forms the jugular foramen (see Fig. A48).

The inferior surface of the pyramid presents the stylomastoid foramen at the base of the mastoid process; it is the outer opening of the facial canal. In front of it lies the slender, often very long styloid process, whose base is partly ensheathed by a plate-like projection of the tympanic portion, the vaginal process. Close to the styloid process is a broad, elongated groove, the jugular fossa, which abuts medially upon the jugular notch and receives the bulb of the jugular vein. In the floor of the groove is the small sulcus of the mastoid canaliculus. On the posterior margin close to the jugular fossa is a small opening, the external aperture of the cochlear canaliculus; in front of this is the large round external carotid foramen and between this and the jugular fossa is a small depression, the petrous fossula, from which a small canal, the tympanic canaliculus, passes through the floor of the tympanic cavity.

The base of the petrous portion forms the medial wall of the tympanic cavity. In the adult it is covered in by the tympanic portion of the bone, so that only a small strip of it is visible at the surface along the petro-tympanic fissure.

The tympanic cavity is an air-containing cavity lying between the petrous and the tympanic portions. The external auditory meatus leads into it from without; its roof is formed by a thin part of the petrous portion, the tegmen tympani, while its floor is formed partly by the petrous and partly by the tympanic portion. Anteriorly and medially the cavity is continued into the canal for the Eustachian tube (canalis musculo-tubarius) and posteriorly and laterally it has opening into it the antrum and the mastoid cells. It contains the three small auditory ossicles, which together with the walls of the cavity will be described in connection with the auditory organ (see here).

The tympanic portion of the temporal bone is a small trough-shaped plate of bone which forms the sides and floor of the external auditory meatus and the lateral wall of the tympanic cavity. It is separated from the petrous and squamous portions by the petro-tympanic fissure (fissure of Glaser), from the mastoid portion by the tympano-mastoid fissure and it forms the vagina of the styloid process.

The temporal bone of the new-born child differs markedly from that of the adult in that the tympanic portion has the form of a ring that is open above, and there is practically no mastoid process. The squamoso-mastoid suture is still quite distinct, separating the squamous portion from the mastoid and petrous portions, which form a single mass. In the course of the first year the tympanic ring becomes the trough-like structure, which at first has in its floor a constant foramen.

The facial canal, mainly for the facial nerve, begins at the bottom of the internal auditory meatus and runs at first horizontally and almost transversely to the axis of the petrous portion to the hiatus of the facial canal. There it bends at a right angle and runs in the medial wall of the tympanic cavity, again almost horizontally, but in the line of the axis of the pyramid, until it reaches the pyramidal eminence of the tympanic antrum (see here). Here it bends to assume a vertical direction and opens by the stylomastoid foramen. From the lower portion of the canal the canaliculus for the chorda, tympani leads to the tympanic cavity.

The carotid canal is a short, but wide canal, situated near the apex of the pyramid. It begins at the external carotid foramen and runs at first vertically, but later bends almost at a right angle so as to run horizontally, and ends at the internal carotid foramen. Small canals, the carotico-tympanic canaliculi, lead from it into the tympanic cavity.

The canal for the Eustachian tube (canalis musculo-tubarius) runs parallel with and immediately adjacent to the horizontal portion of the carotid canal, almost in the axis of the pyramid. It begins as a notch on the anterior angle of the pyramid, between that part of the bone and the squamous portion, and ends on the anterior wall of the tympanic cavity of which it seems to be a direct prolongation. An incomplete horizontal septum divides it into an upper canal for the Tensor tympani and a lower one for the Eustachian tube (tuba auditiva).

The tympanic canaliculus leads from the petrous fossula into the tympanic cavity, where it becomes the sulcus promontorii, and then leaves the cavity by its upper wall to open by the superior aperture of the tympanic canaliculus on the anterior surface of the pyramid.

The very narrow mastoid canaliculus begins as a groove in the jugular fossa, passes through the lower portion of the facial canal and opens in the tympano-mastoid fissure.

The parietal bone is large quadrangular flat bone, convex on its outer surface and concave on its inner. The four borders are

The four angles of the bone are the frontal situated at the junction of the sagittal and coronal sutures, the occipital at the junction of the sagittal and lambdoid sutures, the mastoid at the parieto-mastoid suture, where it occupies the parietal notch of the temporal bone, and the sphenoidal which articulates in the spheno-parietal suture with the great wing of the sphenoid. This last angle is the sharpest.

The outer convex surface presents at the region of greatest curvature the tuberosity and also stronger superior and weaker inferior temporal lines, both of which have an arched course. Below the latter line the parietal forms a part of the temporal surface (see Fig. A44, A45). In this region the squamosal border is rough, being overlapped by the squamous portion of the temporal bone. Near the posterior end of the sagittal border and close to the sagittal suture is the parietal foramen.

The inner (cerebral) surface shows well marked arterial grooves, especially on the anterior part of the bone, produced by the branches of the middle meningeal artery. At the sagittal border there is the one half of the sagittal sulcus and at the mastoid angle one sees a short portion of the sigmoid sulcus. Not infrequently the cerebral surface presents digitate impressions and juga cerebralia and frequently also Pacchionian depressions (foveolae granulares) which may be of considerable depth, especially in middle and old age.

The frontal bone consists of two unpaired portions, the frontal plate and the nasal portion, while the orbital portions are paired.

The frontal plate forms the principal part of the bone. It articulates by its parietal border with both parietals in the coronal suture and by its sphenoid border with the great wing of the sphenoid in the spheno-frontal suture. The outer surface is strongly convex and presents at the middle of each half the tuber frontale. Above the margins of the orbits are two arched projections, the supraciliary arches, and between these the somewhat depressed glabella. The upper border of the orbit separates the frontal plate from the orbital portion. Its lateral part is formed by the zygomatic process which unites with the fronto-sphenoidal process of the zygomatic bone in the zygomatico-frontal suture. From the zygomatic process the temporal line takes origin and separates from the frontal surface a small almost vertical portion, the temporal surface. In the inner half of the supraorbital border are two notches, the medial frontal notch and the lateral supraorbital notch, this latter being frequently converted into a foramen, the supraorbital foramen.

The cerebral surface of the frontal plate possesses in its lower portion a median ridge, the frontal crest. This begins below at a foramen, the foramen caecum, bounded by the frontal arid ethmoid bones in common, and running upwards into the sagittal sulcus. The surface is smooth, except. for some digitate impressions and juga cerebralia, as well as Pacchionian depressions (foveolae granulares). It passes over without sharp demarcation into the cerebral surface of the orbital portion.

The orbital portions are separated from one another by a deep ethmoidal notch which receives the lamina cribrosa of the ethmoid. Each possesses an upper cerebral and a lower orbital surface. The former shows very abundant digitate impressions; the latter is concave and forms the roof of the orbital cavity. It presents on its medial portion a small depression, the fovea trochlearis (occasionally also a trochlear spine), and on its lateral part a shallow depression, the lacrimal fossa, for the lacrimal gland. The borders of the ethmoidal notch are broad and rough since they bear the ethmoidal foveolae, which complete the ethmoidal cells. Furthermore they bear an anterior and posterior groove (or short canal), which serve to form the anterior and posterior ethmoidal foramina.